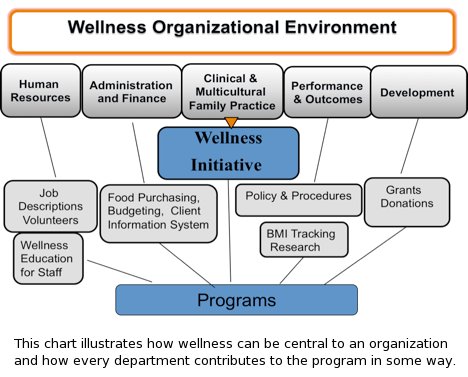

Web ExclusiveChild Welfare Agencies Have Obligation to Client’s Physical Well-Being Fourteen-year-old Alan’s background presented a perfect recipe for unhealthy weight gain. He grew up in a poor neighborhood with neglectful parents mired in substance abuse. Food was scarce in his home; homemade meals were unheard of; and Alan’s “dinner” was often chips and soda from the local convenience store. Alan was placed in state care when he was 12 and later diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Isolation, depression, and poor nutrition had already triggered harmful eating habits and weight gains for Alan, but the side effects from lithium added to his 300-lb weight. After several disrupted foster home stays, Alan was placed in a residential program. The program’s clinicians are striving to create a multipronged approach that will effectively treat and manage Alan’s mental illness, recondition his eating habits, manage his physical health, and resolve his early childhood trauma. A Problem of Epidemic Proportion Obesity is an especially vexing issue for child welfare agencies. A wide range of factors inherent in the socioeconomic, environmental, and even genetic backgrounds of child welfare clients predispose them to the problem. An insufficient knowledge of healthful eating habits, instability among caretakers, and limited access to healthful foods and safe outdoor exercise spaces are issues disproportionately common among child welfare clients. Client’s depression, stress, low self-esteem, and other mental health challenges often trigger overeating. And medications prescribed to improve mental health, such as psychotropic drugs, frequently have metabolic side effects that can further contribute to unhealthful weight gains. Fortunately, child welfare agencies are well positioned to address obesity among clients. As a profession dedicated to helping children at risk, we understand developmental issues, a systems approach to care, and recovery and independence. We’re knowledgeable about the mental health and therapeutic interventions needed to support the population and have expertise working with families impacted by poverty. At The Home for Little Wanderers (The Home), one of New England’s largest nonprofit child and family service agencies, we work with more than 7,000 children and families statewide, including 150 congregate care clients in six group homes and three residential schools. As our clients’ surrogate caregivers, we are conscious of the opportunity and, in fact, obligation to directly impact clients’ overall wellness. With that obligation in mind, we recently launched a wellness initiative, establishing a management plan and creating structures and systems dedicated to improving client wellness, beginning with our congregate care residents. A Holistic Approach

Given these myriad challenges, we created common practice guidelines specific to areas such as our meal service environment, menu planning, and integrating healthful eating and physical activity into treatment planning. Central to these guidelines is a policy establishing wellness committees. These committees provide very useful forums from which to gather input from different sources, set goals, and track achievement. Client Assessment and Treatment As part of The Home’s initiative, we revamped our initial client health assessment questionnaire to include several new questions concerning physical activity, such as how often someone is active and what kinds of activities, and nutrition, such as eating habits, as well as standard health history questions. We also modified our client information system to include a field for data from a monthly measurement of client’s body mass index (BMI) instead of just height and weight. A nurse administered the initial assessment and measured client BMI monthly. The results of these assessments have been vitally important in evaluating clients’ needs; making appropriate referrals for healthcare, nutritional, and other treatment interventions; and measuring client progress. Education and Modeling Wellness One of the first wellness educational ventures The Home tackled involved an online learning course. We created a two-part wellness course that briefly covers an array of topics, such as the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, food safety, healthful cooking methods, and physical activity strategies. At first we required only the staff in our congregate care program to pass both parts of the course. Now all current staff members are required to take and pass both courses, with successful completion being linked to their annual performance evaluation. The course is also a required part of training for all our new hires. In addition to more structured learning, dietitians, nurses, or educated staff members can make important contributions to wellness education. We hired a part-time dietitian to provide information and support to clients and have augmented that support through one-on-one and group wellness discussions led by other knowledgeable staff. Nutrition education can involve games, tactile visual aids for those who learn by doing, and even taste testing with residents and staff. Foodservice Systems If an agency doesn’t have standardized processes for food purchase, individual group homes may be purchasing food from different vendors or even from the local grocer. However, by engaging a single food vendor or meal service company, agencies can reduce food costs, streamline ordering and tracking, and ensure adherence to nutritional guidelines. At The Home, we had been purchasing food from 11 different vendors for our nine congregate care programs, and staff members were often supplementing supplies with trips to local grocery stores. As part of our wellness initiative, we began to centrally order food for all residences, a move that simplified food budget projecting and tracking. Of course, centralized food ordering is predicated on the idea that meal planning will be centralized as well. Meals that are planned based on dietary guidelines and are part of a cyclical menu can be planned by a staff dietitian. Client and staff input should be solicited, and ethnic food preferences considered. The Home’s dietitian created a four-week cycle menu and increased the use of whole grains, low-fat dairy, fruits, and vegetables—changes that didn’t sit well with all clients. However, our commitment to gathering input from clients through menu brainstorming sessions at each group home, administering an annual client menu survey, and offering taste testing opportunities has helped clients choose healthful foods that they enjoy. Who’s Cooking? Work Going Forward — Peter Evers, LICSW, is vice president of program operations at The Home for Little Wanderers in Boston. — Mary Barber is wellness project manager at The Home for Little Wanderers. |