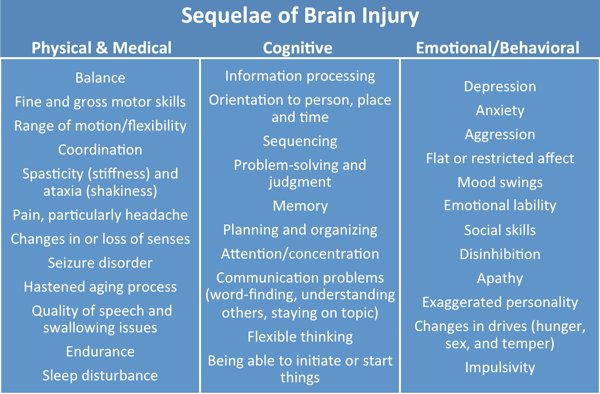

Web ExclusiveBrain Injury — Important Facts and Implications for Social Work Practice Roberta is a bright, high-energy, fun-loving, career-oriented woman in her early 30s who worked as a pharmaceutical sales representative. Roberta’s ability to multitask and think quickly and her dedication to working long hours put her on the fast track to project leader of the sales team. On one winter day while traveling to see a client, Roberta’s car slid on a patch of ice, went off the road, and crashed into a ditch. Roberta sustained minor physical injuries and a bad concussion. She did not lose consciousness. Her family and coworkers believed, as did Roberta, that while this was a serious accident, she would recover fully. The expectation was that she would be back to her usual, highly productive self in a matter of weeks. After several months of ongoing headaches, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and decreased motivation to return to work, her family started to wonder what was wrong with Roberta. Why didn’t she just get over the accident and go back to her life? Why was she so unmotivated? What her family didn’t understand was that Roberta’s symptoms were related to her concussion and that Roberta had actually sustained a brain injury. Brain injury refers to the death of brain cells and the disruption of neural pathways that can change the way a person thinks, feels, and/or acts. A brain injury can be caused by an outside force, such as a bump, blow, or jolt to the head related to an accident, fall, or violence, or to a change in air pressure, such as a blast injury. Brain injuries can also result from neurologic diseases, lack of oxygen to the brain, or penetrating wounds like gunshots (Rutland-Brown, Langlois, Thomas, & Xi, 2006). Brain injury is increasingly recognized as a health concern with lifelong implications; however, it continues to be referred to as the “silent epidemic,” perhaps because awareness about brain injury, although improving, continues to be limited. It is estimated that an average of 1.7 million individuals sustain brain injuries each year (Coronado et al., 2011), which translates to about one person every 23 seconds. Brain injuries are most likely to occur in the very young (under the age of 5), followed by adolescents (ages 15 to 19) and adults over the age of 75 (Coronado et al.). Brain injury has a higher prevalence than HIV, breast cancer, and multiple sclerosis combined. Brain injury is also frequently undiagnosed and underreported (Leibson et al., 2011). Brain Injury Sequelae

Clearly, brain injury can impact all aspects of a person’s life. An individual’s identity in his or her family, friendships, and workplace are often affected. Alarmingly, it is estimated that 60% of people with brain injuries are never able to return to their prior employment (van Velzen, van Bennekom, Edelaar, Sluiter, & Frings-Dresen, 2009). Many lose their friendships and spouse or partner. People with a brain injury often experience and report social isolation, feelings of loneliness, and loss of friendships as a primary problem (Temkin, Corrigan, Dikmen, & Machamer, 2009) as well as an inability to participate in their hobbies and leisure activities. Similarly, family members of these patients often experience significant stress, including the development of significant psychological symptoms as well as the loss of social support (Vangel, Rapport, & Hanks, 2011). Social workers can play a vital role in helping individuals and their families to accept and learn how to adapt to the inevitable changes that result from brain injury. Making an Impact Recognizing At-Risk Populations and Symptoms While a history of coma indicates the likelihood of a brain injury and the potential for long-term impairment, short losses of consciousness, or alterations, can also indicate the presence of a brain injury. There is no medical test that can predict a person’s prognosis based on a specific injury. It is important to understand that even if an MRI or CT scan does not reveal any physical brain changes, the injury may still affect the person. The social worker should take into consideration a client’s history, as there may have been instances of head trauma not documented in the person’s medical record, as well as look for possible symptoms of brain injury. Screening Questions • Have you ever been hit in the head? • Have you ever lost consciousness? • Have you ever had a concussion? • Do you, or did you ever, play contact sports? • Have you ever been in a car accident? • Have you ever been in a physical fight or a victim of violence? • Are you a veteran? Were you ever injured in service? If an event with the potential to cause head trauma is found, social workers should follow up with questions about the immediate effect of the trauma, including amnesia, disorientation, or confusion, and then with questions about its impact on functioning in the following weeks, months, and even years. The Ohio Valley Center for Brain Injury Prevention and Rehabilitation, in conjunction with BrainLine, has developed a screening tool available at www.brainline.org. Helpful Referrals Each state has a Brain Injury Association, organized by the umbrella organization Brain Injury Association of America (www.biausa.org). These organizations often have online resources that contain provider information, family support services, and general brain injury education. Children with brain injuries can qualify for specialized services until the age of 21 through their school districts with an individualized education plan. This information is imperative for school social workers to know so they can educate parents, teachers, coaches, colleagues, and students. They can also advocate for needed services and make necessary referrals. School social workers should also be aware of the special situation concussions can pose for students and schools. While a child can completely recover from a concussion, it is often recommended that a child’s return to school be gradual, following a period of complete rest at home. Social workers can play a critical role in gathering information from family and physicians and ensuring that all school staff are aware of medical recommendations about concussion management and restrictions (e.g., recess, physical education, sports). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has many valuable resources on concussion, including free tool kits and checklists (http://www.cdc.gov/concussion). Finally, social workers should be aware of the adjunct resources in their community that clients may need to access, including assistance with transportation, housing, legal problems, education and/or employment, attendant care, assistive technology, and financial support. Quick Tips for Working With Individuals With Brain Injury • Have a family member present in sessions. • Speak simply and ask direct questions. • Avoid long, complicated discussions. • Check the client’s understanding of the information presented, making sure to allow time for processing. • Offer breaks. • Provide appointment reminders. • Be careful with humor and your personal space. Additional resources are provided in the table below:

Final Thoughts — Jennifer Fleming, MA, LPC, CBIS, is a day program specialist at ReMed in Paoli, PA. — Natasha McVey, MSS, LCSW, CBIS,is a rehabilitation case manager atReMed. — Madeleine Shusterman, LCSW, CBIS, is a clinical specialist at ReMed. — Eli DeHope, PhD, LCSW, BCD, is a professor of undergraduate social work at West Chester University of Pennsylvania.

References Rutland-Brown, W., Langlois, J. A., Thomas, K. E., & Xi Y. L. (2006). Incident of traumatic brain injury in the United States, 2003. Journal of Head Trauma and Rehabilitiation, 21(6), 544-548. Leibson, C. L., Brown, A.W., Ransom, J. E., Diehl, N. N., Perkins, P. K., Mandekar, J. et al. (2011). Incidence of traumatic brain injury across the full disease spectrum: A population-based medical record review study. Epidemiology, 22(6), 836-844. Temkin, N. R., Corrigan, J. D., Dikmen, S. S., & Machamer, J. (2009). Social functioning after traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 24(6), 460-467. Vangel, S. J., Rapport, L. J., & Hanks, R. A. (2011). Effects of family and caregiver psychosocial functioning on outcomes of persons with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 26(1), 20-29. van Velzen, J. M., van Bennekom, C. A., Edelaar, M. J., Sluiter, J. K. & Frings-Dresen, M. H. (2009). How many people return to work after acquired brain injury?: A systematic review. Brain Injury, 23(6), 473-488. |