Media/ArtsThe Animation Project — Helping Youths Create Success Stories In 2007, Robert, a 16-year-old from the Bronx, was arrested for robbery and placed in the Center for Alternative Sentencing and Employment Services (CASES). The program works with New York courts to offer youths rehabilitation opportunities such as GED training as an alternative to incarceration. Unfortunately, Robert was uninterested in the required classes and could not wait to get home each day.

The program Robert participates in is called The Animation Project (TAP), and it was founded by Brian Austin, a 3-D animator and art therapist. TAP works with small groups of adolescents using the program 3D Studio Max to animate a story created by the class. Austin conceived the program while he was working on his master’s degree in art therapy at New York’s School of Visual Arts (SVA). In the late 1980s, Austin earned his undergraduate degree in painting from SVA and, like many art school graduates, was unable to make a living in the field. Austin found work in the rising industry of computer animation, which was in its infancy. He soon carved out a career creating commercials and broadcast graphics, teaching animation in colleges, and even coauthoring a how-to book. After 15 years of working exclusively on computers, he burned out and realized he missed painting. He had always had an interest in the therapeutic values of art and enrolled in SVA’s master of art therapy program. Though intent on using a traditional approach when he started the program, he found when he mentioned his computer art background to faculty, they encouraged him to use it as a medium. This new focus culminated in his thesis, a site study at New York Foundling, a foster care organization. In this setting, Austin created the class model TAP still uses today. Pleased with how the study went, he realized computer animation can be a significant therapy tool. “I looked at it and realized the backbone of the whole thing is that a lot of the lessons are built into the medium,” he explains. “With animation, you can’t just sit down and do it and be finished in half an hour.” Austin realized that the delayed gratification and planning that go into every piece of animation make it well suited for adolescent development. “Their impulse is to do things quickly, but they’re interested enough in the technology to sit with it and wait.” After graduating, Austin wanted to continue this form of therapy and began pitching the idea to programs he felt might be interested. One of the first places was CASES. The first year Austin was involved with CASES, he would go with only a laptop and a projector and run the groups himself. Thanks to grants from groups such as the Entertainment Software Association Foundation, Austin now has an art therapist and animator to colead each group. In addition to CASES, TAP works with youths at Year Up, an urban development program that arranges career training and internships for young adults aged 18 to 24. I was able to observe a session with a Year Up group in TAP’s main office near Wall Street in lower Manhattan. The group was colead by Karen Gibbons, an art therapist, and animator Dan Ruzeu. Gibbons began the session by reviewing a production schedule tacked to the wall, which laid out everything the group hoped to accomplish. The youths, who come to the offices twice a week right after their internships, were excited and started suggesting story ideas. When one girl mentioned zombies, the other students lit up. Gibbons used this story idea to steer the group toward real issues they struggle with but may not be able to verbally address.

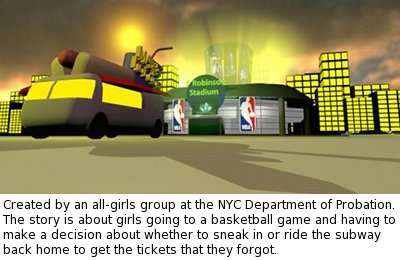

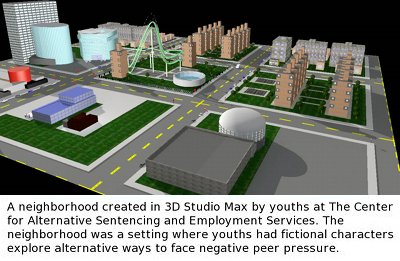

Although none of the group members had worked in 3D Max before, they are all computer savvy, much like most in their age group. It was this fact that ultimately drew Austin’s focus back to computer animation. In the span of 45 minutes, each group member has turned a square polygon into a house with a pitched roof and side garage. As Gibbons says, “Video games, movies, and print media are probably the main art forms these young people have been exposed to. Media like pastels and paints would be unfamiliar.” The group will spend the next four weeks building assets in 3D Max developing their story. As the weeks progress, they will begin dividing duties: One person may build the characters while another builds the setting of a scene. “My concept was always that it should be youth-directed stories. That can be difficult terrain to navigate because of what these kids lives are like,” Austin says. While the group I observed did not consist of court-involved youths, groups at the other sites TAP works with are court involved. The stories pitched are often about crime and drugs, which can make many criminal justice programs hesitant because they prefer to see stories reflecting socially acceptable behavior. TAP sets some ground rules of no gratuitous violence, abuse, or ridiculing of any specific group or person. One may think giving a group of 16-year-olds total freedom could lead to some immature story telling, but the films produced by the program are surprisingly insightful. The opportunity to have their voices heard is only part of what TAP students receive through the classes. When they learn a program such as 3D Max, they are learning a marketable skill. While Austin knows the value of more traditional forms of art therapy, such as painting or drawing, he also knows firsthand the difficulty of finding a job with a painting degree. With TAP, youths are gaining not only knowledge of 3D Max but greater comfort and confidence in learning software programs. Helping youths discover they can make a living with these programs was another of Austin’s goals from the start. “Whether or not you’re ever an animator, you’ll never face another piece of software again and say, ‘I can’t do it.’” TAP students can now share the skills they have learned. Recently, TAP has begun organizing screenings of the students’ work where people from outside the programs are invited to watch the films for an evening. After TAP’s first screening last spring, an attendee who liked one group’s animation hired its three creators to design a logo for his youth arts program. One of the three was former CASES member Robert. More than one year ago. Austin was able to get Robert, now 21, an internship with a postproduction house in New York City. Robert was nervous initially, but with encouragement from Austin and confidence gained through the skills he learned in the group, he began to feel comfortable. After helping with office tasks, he was soon involved in more creative areas, eventually working on graphics for an NBC special. When he started at CASES, Robert was dismissive and uninterested. Now he is thrilled to be part of the team. His favorite moment at his internship was when he was given a company sweatshirt at a holiday party. Though his internship ended, he has been invited back on occasion and continues to teach a Photoshop class with TAP. Currently, he is assembling his portfolio to submit to art schools, where he plans to continue studying computer animation. — Greg Condon is a freelance animator and writer based in New York City. |

Around this time, CASES was looking for new ways to connect with the youths and had recently launched a new art therapy initiative using animation. The experimental class consisted of a group of teenagers working together to create a story based on their experiences and bringing it to life using computer animation software. Robert signed up out of obligation but soon found himself committed to the initiative and learning fast. Five years later, he is teaching the class.

Around this time, CASES was looking for new ways to connect with the youths and had recently launched a new art therapy initiative using animation. The experimental class consisted of a group of teenagers working together to create a story based on their experiences and bringing it to life using computer animation software. Robert signed up out of obligation but soon found himself committed to the initiative and learning fast. Five years later, he is teaching the class. The topic of fearing zombies lead to a discussion of the youths fearing the future with their internships. Gibbons, who has provided art therapy with various artistic materials, finds the use of computer animation effective particularly when working with slightly younger groups. “Developmentally, adolescents are well known for being resistant to emotional exposure and wary of situations that do not allow control,” she says. Working on a computer adds a level of familiarity for them, she believes. “The client is in control and has the added protection of the computer screen. I find that the groups work very well with this protection in place.”

The topic of fearing zombies lead to a discussion of the youths fearing the future with their internships. Gibbons, who has provided art therapy with various artistic materials, finds the use of computer animation effective particularly when working with slightly younger groups. “Developmentally, adolescents are well known for being resistant to emotional exposure and wary of situations that do not allow control,” she says. Working on a computer adds a level of familiarity for them, she believes. “The client is in control and has the added protection of the computer screen. I find that the groups work very well with this protection in place.”