|

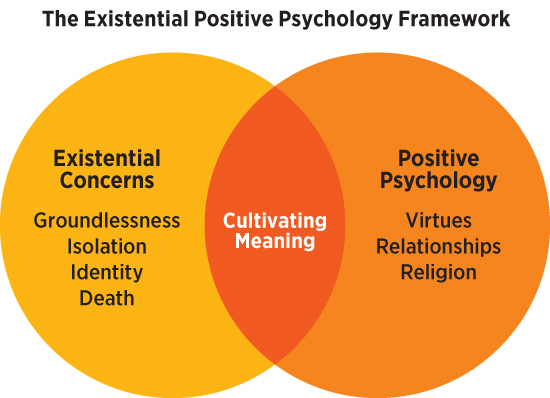

Suffering is an inescapable part of life. Some suffering is so profound, so violating, or so dogged that it fundamentally changes people in indelible ways. But therapeutic approaches that treat suffering as a problem to be fixed are incomplete. In their book The Courage to Suffer, Daryl and Sara Van Tongeren introduce a new therapeutic framework that helps people flourish in the midst of suffering by cultivating meaning. Drawing from scientific research, clinical examples, existential and positive psychology, and their own personal stories of loss and sorrow, the Van Tongerens show how those afflicted with suffering can still choose to live with hope while acknowledging the reality of their pain. The following is an excerpt from The Courage to Suffer. Clinical work has long focused on alleviating suffering. However, not every therapeutic model is designed to help those in persistent, recurring, or unsolvable suffering. Many perspectives approach mental health concerns as discrete negative events that can be directly resolved through cognitive adaptation, emotion regulation, or behavioral modification strategies. Boiled down to its most basic level, many clinical approaches view suffering as a problem to be fixed, and then, once the symptoms subside, disregard the effect of the event itself. This strategy falls short, however, when the event and its effects have fundamentally changed the individual’s life and cannot be resolved. There is no fixing death, infertility, loss of a dream, or the permanent shift of one’s identity. Instead, these approaches must account for deeply painful situations that alter your client’s life in ways that cannot be reversed or solved. Our framework is designed precisely for such situations. Put succinctly, we posit that suffering is an inherent part of life that must be engaged. And we suggest that your clinical approach embody that truth. Overview of Framework Existential approaches to psychotherapy, popularized by individuals such as Viktor Frankl and Irvin Yalom, contend that anxiety and suffering arise, in part, from the persistent isolation of all humans and the inherent meaninglessness of the world, where the only certainty is death (Frankl, 1959; Yalom, 1980). Each person is inherently alone and is wired to find ways to connect with others and create meaning while they are alive. Part of the existential process is accepting, and coming to terms with, these givens of human existence. Our approach provides a pathway for exploring the depth of your client’s situation by examining what central fears are uncovered by their suffering and how it may be affecting their ability to flourish. As people identify core features of human existence as root causes of their suffering, they can learn to create meaning from within, rather than expecting to find meaning from the outside—regardless of their circumstances. Meaning is also a central feature of the positive psychology movement, which developed as a response to the majority of psychological research and clinical work that had focused solely on viewing people through the lens of mental disorders and abnormal functioning (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Psychology had become narrowly focused on the negative: distress, dysfunction, disorders, and disease. But this focus on the negative provides an incomplete view of human nature. Positive psychology addresses that “other half” by emphasizing how character strengths, virtues, and meaning contribute to the good life. In short, whereas most other psychological perspectives help people cope with mental illness, positive psychology helps people cultivate full and flourishing lives. The synergistic blend of the existential psychology perspective and the positive psychology perspective creates a shared goal: building meaning in all circumstances. Drawing from existential and positive psychology, our approach examines the deep, underlying existential concerns that suffering exposes, while focusing on building meaning and promoting a full, whole life that is marked by authenticity and concern for others (Wong, 2009). This approach requires balancing both motivations of depth and growth: Without sufficient depth, your clients will not fully address the core root of their suffering; and without sufficient growth, your clients may stagnate and become overwhelmed by feelings of hopelessness, depression, and despair. Your role as therapist is to help your clients engage both motivations by helping them cultivate meaning. This intersection of perspectives is depicted in the accompanying figure.

Defining Terms: Suffering, Meaning, and How the Two Relate The Difference Between Pain and Suffering However, other forms of emotional pain are qualitatively different. Whereas pain may have some form of a solution, suffering is persistent and may not be resolvable. Some suffering is so profound, so violating, or so dogged, that it fundamentally changes people in indelible ways and forces them to come to terms with core existential realities of life. Situations like these are unexplainable or violating, persistent and enduring, and fundamentally life-changing. You can experience pain without suffering, but you cannot experience suffering without pain. Our approach is designed to help you work with clients who are suffering. Consider a client who seeks support after the expected death of a parent from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a genetic and heritable disease that also has implications that affect not only your client but the immediate family as well. The death of their parent elicits existential concerns about their own death and the lives of their children. You could attempt to employ a CBT approach and help the client reframe how they think about dying or help them cope with the emotional distress of losing a parent, but you would be working from a limited perspective that only addresses a resolution from the aspect of losing a parent. What do you do with the very real idea that your client’s own health is at risk and that they will have to live with that uncertainty? Our approach acknowledges that the pain your client feels is valuable and must be wrestled with and integrated, not removed. Instead, your client can learn to bear this pain. What Is Meaning? People experience significance when they feel like they have worth, value, and that they matter or feel connected to something larger than themselves. People usually feel significant when they have reciprocal relationships, when their work is consequential, and when they are making a positive, lasting contribution to the world. The central question pertaining to significance is: Do I matter? People achieve a sense of purpose when they have broader intentions toward which they can place their energy and effort. A sense of purpose gives people a reason for their actions and helps frame your client’s sense of identity. The central question pertaining to purpose is: Why am I here? Each facet of meaning acts as a protective factor during times of suffering. Coherence translates events in ways that make sense; significance helps people transcend themselves and connect with others; and purpose transforms experiences, including pain and suffering, into something greater. — Daryl R. Van Tongeren, PhD, is an associate professor of psychology at Hope College in Holland, MI. A social psychologist, he has published more than 175 scholarly articles and chapters on topics such as meaning in life, religion, virtues (including forgiveness and humility), relationships, and well-being. More information is available at darylvantongeren.com and Instagram @darylvantongeren or Twitter @drvantongeren. — Sara A. Showalter Van Tongeren, LCSW, is a licensed clinical social worker in Michigan and Virginia, and a graduate of the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Social Work. She has more than 12 years of clinical social work experience in settings such as private practice, foster care, inpatient hospitals and outpatient medical clinics, domestic violence shelters, and behavioral health. More information is available at saravantongeren.com and Instagram @theexistentialtherapist.

References George, L. S., & Park, C. L. (2017). The multidimensional existential meaning scale: A tripartite approach to measuring meaning in life. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12, 613-627. Martela, F., & Steger, M. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11, 531-545. Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5-14. Wong, P. T. P. (2009). Positive existential psychology. In S. Lopez (Ed.), Encyclopedia of positive psychology (Vol. 1), pp. 361-368. Wiley-Blackwell. Yalom, I. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books. |

In The Media: New Book Gives Hope to Those Suffering

In The Media: New Book Gives Hope to Those Suffering