|

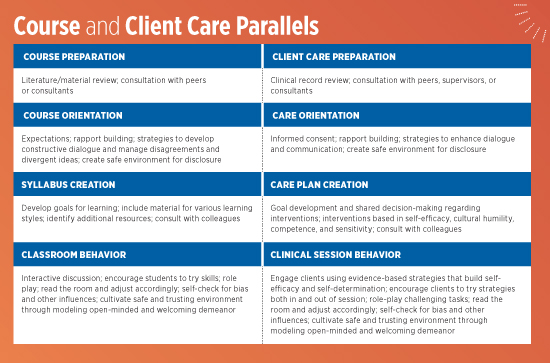

Educators offer strategies to create experiential learning opportunities in the classroom. As licensed clinical social workers with more than 20 years of practice experience who are faculty at a graduate social work program, we share a common belief in the importance of students’ access to experiential learning opportunities, which forms the basis of social work practice. To achieve this aim, we develop learner-centered strategies that help students connect to course material through practical experiences. Also, we model practice behaviors that reflect the standards of healthy professional relationships that comprise the foundation of experiential learning. This article outlines the specific strategies used to create experiential learning opportunities that closely resemble the skills students will need to engage clients in effective social work practice. The goal is to stress the importance of not only “talking the talk” in social work teaching, but also “walking the walk”—that is, creating a learning environment that mirrors practice by immersing students in the behaviors they will need to learn to successfully engage clients. These strategies and parallels are outlined in the accompanying table.

Modeling Preparation for teaching may include review of the literature as it relates to the subject matter and consultation with other instructors to ensure the course is innovative and creative, and includes multiple learning formats. Demonstrating these parallels in detail helps students to fully understand the important role of preparation in clinical social work practice. As required by NASW’s Code of Ethics, practitioners recognize the importance of self-care in working with clients, beginning in the preparation phase and continuing throughout the process. To help students understand the ethical principles behind self-care, we create syllabi that stress self-assessment and guidance toward resources for those students who may experience reactions to sensitive course content. Help-seeking is encouraged, and parallels are drawn between caring for self and caring for clients and the need for ongoing self-assessment. Course and Client Care Orientation As a group, we discuss course expectations with students, just as we would discuss with clients the expectations for participation in care (informed consent). In client care, we view assessment as an ongoing process. In the classroom, we use the syllabus as a working document, intended to be flexible to change. This ongoing or flexible nature of the process is based primarily on feedback solicited from both students and clients about how they perceive things to be going and what adjustments are needed. Modeling this ongoing worker/client dialogue with students in the form of syllabus flexibility helps the students see the importance of checking in with clients out of concern for their growth, which enhances the clinical relationship. We model several evidence-based strategies to help students gain knowledge of these practices, including framing our dialogue in motivational interviewing, a person-centered style of dialogue. Course content is based on recovery model care concepts as defined by major mental health organizations such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which emphasizes self-direction and autonomy. Modeling these best practice concepts empowers students to take ownership of learning outcomes. It’s comparable to clients understanding their collaborative role in their care. Syllabus and Care Plan Creation This process mirrors the discussion of evidence-based practices we may employ to engage with clients. With both, we offer choices among expertly chosen materials. The goal is to remove the potential for clients and students to feel intimidated by the process whereby they perceive the material to be accessible and the environment to be safe, inclusive, and accommodating. As a result, both students and clients gain self-efficacy and a sense of agency over the material and/or process. Just as we may rely on one particular (comfortable) intervention with clients, we may feel more comfortable with a particular “go-to” way of teaching with students. However, it’s important to recognize that clients and students are the priority and to ensure that they are provided with a variety of options. Culturally sensitive, humble, and competent assignments and learning opportunities that respect a variety of world views inspire students to learn from each other and instructors to learn from students. These considerations are also important in client care. Again, we may be uncomfortable breaking from our routine; however, students will learn the importance of this strategy in their care with clients if we have clearly modeled it in our teaching. Classroom and Clinical Session Behavior Rather than sticking to prescribed and predetermined ideas, we adjust as needed. We make alternative opportunities available based on our perception of progress. For example, adjustment may be made to goals and objectives, pacing, timing, or structure of assignments. We consistently self-assess, asking ourselves questions such as, “What is my bias on this topic, or with this client? Am I presenting this in a biased way? How is this being perceived by my client or students?” We cultivate autonomy by trusting students and clients and respecting their right to self-determination. We demonstrate boundaries, self-awareness, and use the NASW Code of Ethics and the SAMHSA recovery model as our framework for discussion, including the positive regard of all students and clients. Experiential Learning Outside of the Classroom Examples of Course Assignments Students have the flexibility to choose the event, reflect on their attendance, and discuss what they learned. For evaluation of the assignment, students choose to complete a written paper or deliver an oral presentation with the professor. Students have reported that choosing to meet with the professor provided a chance for them to step outside of their comfort zone, which is similar to how a client’s comfort may feel challenged during a session. Therefore, this assignment met both an academic and practice skill achievement expectation. In our social work practice courses, students have many opportunities to learn skills, such as motivational interviewing, that translate to having dialogue with and being present for others, including those in their personal lives. We reiterate that the communication and intervention skills gained, including distinguishing between open and closed questions, reflection, and mindfulness, are valuable tools to use in their everyday lives. In the classroom, we discuss how being present for others in their outside lives ensures they understand that the office is not the only setting where we engage in these processes. We encourage real-world experiences outside of the classroom and ask students to bring those experiences back into the classroom. Recognizing the ebb and flow of interest, skill acquisition, and overall learning that occurs both in care with clients and in the classroom with students, we consult with each other throughout these and other experiential activities. This consultation helps us keep things fresh, creative, and innovative. We connect with each other across courses, with colleagues at other universities, and with current social work practitioners to ensure the material’s relevance. A Well-Rounded Approach We believe that social work curricula, unlike many other disciplines, require more than lecture to deliver course information. We believe in delivering curricula in the frame of lived experiences and through demonstration and modeling, affording students multiple opportunities to practice what they learn throughout their education. Without applying a practice framework at the onset, there may be missed opportunities for students to understand social work is not just an occupation but also a way of being present for others in helping them lead self-directed lives. Therefore, we advocate for the mirroring of these practice behaviors from the moment we meet students through demonstration, face-to-face interactions, experiential learning activities, and selection of relevant course material. Drawing parallels to client care through experiential learning prepares students for best practices and helps develop reciprocal and balanced client relationships. We utilize a systematic yet flexible approach by working closely with individual students in a learner-centered manner while also teaching to the collective whole. We demonstrate that we are comfortable with our own vulnerability and strive to be our authentic selves. By encouraging this behavior among our students, we promote their emotional growth and intelligence. We create a show-vs.-tell environment through experiential learning, just as we hope our students will create with their future clients. — Kathryn D. Arnett, DSW, LCSW, CADC, is an assistant professor in a master of social work program. She earned a doctorate in clinical social work from the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Policy and Practice and practiced social work for more than 20 years with a specialty in alcohol and drug addiction. — Courtney J. Lynch, PhD, LCSW, is an assistant professor in a master of social work program and practiced social work with a specialty in child welfare and child and family mental health for more than 15 years. The views expressed in this article do not represent the views of any organizations to which the authors are affiliated.

Resources Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Causes and treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Beck Institute. (2021). What is cognitive behavior therapy (CBT)? https://beckinstitute.org/get-informed/what-is-cognitive-therapy/. Haidt, J., Lukianoff, G. (2019). The coddling of the American mind: How good intentions and bad ideas are setting up a generation for failure. Penguin Books. Miller, R., Rollnick, S. (2012). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. 3rd Ed. The Guilford Press. National Association of Social Workers (2021). Highlighted revisions to the Code of Ethics. https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Highlighted-Revisions-to-the-Code-of-Ethics. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2020). Recovery and recovery support. https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/recovery. |

Practice-Informed Teaching in Social Work Education

Practice-Informed Teaching in Social Work Education