|

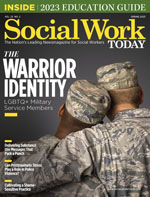

The Warrior Identity: LGBTQ+ Military Service Members US military service members are often associated with a warrior identity.1 The image of a lone male soldier on the battlefield traditionally has been reinforced by recruiting initiatives and military imagery to match that social construction. However, our perceptions and expectations of who participates in military service is changing. The number of LGBTQ+ young adults and adolescents is increasing. As many as 1 in 5 people in Generation Z identify as LGBTQ+, and 1 in 20 identify as transgender alone.2,3 For social workers who specialize in work with veterans, these are important data to inform our practice, as Generation Z represents the greatest number of incoming recruits into the United States military.4 Therefore, the question should be asked: What policies have the US military implemented to protect our LGBTQ+ service members and veterans? Demographics of LGBTQ+ Military Personnel According to an analysis of US census and military enlistment data, credible estimates indicate that approximately 79,000 LGBTQ+ service members are serving in the diverse branches of the US armed forces, and an additional 1 million LGBTQ+ individuals are identified as veterans.5,6 Precise statistics related to the exact number of LGBTQ+ service members and veterans have not been available due to the legacy of discrimination within the culture of the Department of Defense, including the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). As the largest health care provider for LGBTQ+ community members in the United States, the VHA has responded to calls to improve data collection related to health disparities experienced by LGBTQ+ service members and now includes questions related to self-identified gender identity and sexual orientation within VHA medical records.7,8 However, several quality improvement studies have shown that these identifier fields are not completed by the majority of medical providers, and transgender veterans are often less comfortable than cisgender veterans to answer any questions related to their gender identity.7 Despite a reluctance to disclose gender identity that pervades military culture and the armed services’ history of harmful LGBTQ+ exclusionary policies, it’s well documented that LGBTQ+ community members have been serving in the US military since the Revolutionary War.9 Additionally, research has shown that transgender persons actually serve at higher rates than expected from the general population, with recent research showing that up to 20% of transgender persons have a history of military service.4,10 There are an estimated 6,000 to 15,500 transgender service members and 134,000 transgender veterans.4 It’s important to consider intersectionality in demographic discussions of health care for the LGBTQ+ communities, given the historical impact of structural racism in the VHA and the high overlap of LGBTQ+ identity with racial and ethnic minoritized identities in the United States.11,12 Unfortunately, there are scant data examining health outcomes in military personnel that address the intersectional experiences of those who hold both an LGBTQ+ identity and a racial or ethnic minoritized identity. Based on the existing literature on race and ethnicity in military personnel, it would be expected that LGBTQ+ community members of color would increasingly be affected by social determinants of health compared with white LGBTQ+ military personnel.13,14 While there is heterogeneity among studies in categorization and representation of race and ethnicity, it appears Indigenous or Black and Hispanic military personnel postdeployment are at particularly high risk for the adverse psychosocial outcomes of structural disparities within the military.15 More research is needed to examine the unique health care needs and disparities experienced by LGBTQ+ military personnel from communities of color. Historical and Current Policies for LGBTQ+ Military Personnel Department of Defense policies have often criminalized LGBTQ+ identity.17 In 1981, the US Department of Defense issued a policy that noted: “Homosexuality is incompatible with military service.” As a result, many LGBTQ+ service members were pressured to exit their military service on their own accord or were victims of entrapment by other service members in order to end their military service. In 1993, the Clinton administration issued a directive to the Department of Defense known as Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (DADT), which prohibited military officials from asking potential recruits and active military service members about their sexual orientation, but did not include any specific directive related to gender identity. During the era of DADT, service members who shared their sexual orientation or gender identity publicly were discharged with less than honorable status. It’s estimated that more than 12,000 service members were dishonorably discharged prior to the repeal of DADT.18 The 2011 repeal of the DADT policy ended the ban on open lesbian, gay, and bisexual military service members but was not inclusive of transgender service members. A transgender ban on military service persisted until 2016 (and again from 2019 to 2021) but was rescinded in 2021 to permit those who do not identify with their biological sex to both enlist and serve in the military. Despite these examples of more progressive policy related to permission to enlist and serve openly in the armed forces, the legacy of the Department of Defense’s history of exclusionary practice remains embedded in many aspects of military culture. The military’s legacy of harm directed toward LGBTQ+ military personnel has contributed to the widespread problem of less than honorable discharge status for a large number of veterans who identify as LGBTQ+ community members.9 Honorable discharge status is an important factor for healthy aging, as it entitles retired service members to income, health care, supportive services, and other resources that can help provide needed support for veterans across the lifespan. Therefore, retirement from the armed forces with honorable discharge status can serve as a protective factor against risk factors disproportionately experienced by LGBTQ+ veterans, such as housing instability, food and financial insecurity, substance abuse disorders, poor health outcomes, and mental illness.19,20 While the exact number of veterans who have been discharged due to their LGBTQ+ identities with less than honorable status following successful and meaningful military careers is unknown, it’s believed that more than 114,000 LGBTQ+ service members have been dishonorably discharged since World War II.21 On the federal level, the option to improve and expedite the process for application for status upgrade was promised on the 10th anniversary of DADT in 2021 for those LGBTQ+ veterans discharged with less than honorable status. However, since that time, veteran advocacy groups report that most LGBTQ+ veterans who chose to apply are still awaiting a status upgrade and have not been able to access federal benefits.22 On the state level, legislation through Restoration of Honor Acts has been passed in several states to authorize the restoration of some state-based veteran benefits to those who were other than honorably discharged due to LGBTQ+ identity and for those who have experienced mental health problems due to PTSD and sexual military trauma. Restoration of Honor Act states such as Rhode Island, New York, Connecticut, Illinois, Colorado, New Jersey, and California have also increased outreach to LGBTQ+- and veteran-serving community agencies in an attempt to reach those unfairly discharged.23 While state level benefits vary from state to state, benefits are limited to the state in which the veteran applied and are not transferable across state lines. More importantly, Restoration of Honor Act eligibility does not change a veteran’s official status of discharge federally, which instead requires review by the Department of Defense. These state policies do not guarantee increased access to federal benefits from VA, such as health care, home loans, pension, or military burial.22 Many LGBTQ+ service members who may be eligible continue to be unaware that they have the ability to apply for discharge upgrades.8 For some veterans, this information may not be readily available, or they may not have access to this type of assistance. Many veterans have found the application process complicated and onerous or retriggering of the trauma they experienced while in the military and related to their discharge. Impact of LGTBQ Identity on Military Service Psychosocial Health of LGBTQ+ Military Personnel The adverse psychological outcomes observed in military personnel have been attributed to a combination of various psychosocial stressors introduced within the unique lived experiences of military service members and veterans. First, military service members experience high rates of trauma, both military and nonmilitary related. These experiences include combat-related trauma, housing instability, military sexual assault, and a high incidence of reported histories of childhood abuse or intimate partner violence.28,29 Second, military service introduces disruptions in the service members’ previous psychosocial support systems, such as family and friends, both during active service and when returning home. Following completion of military service, social exclusion for veterans often occurs as a result of mental health sequelae of trauma experienced during active service.28,29,34 This transition from active service to veteran status is a particularly vulnerable time for military personnel, especially for those with physical impairments from their time in service.29,35 Third, negative coping mechanisms, such as eating disorders and alcohol and substance misuse, are more prevalent in military personnel. These adverse health behaviors mediate the relationship between military service and increased risk for mental health disorders, particularly higher among LGBTQ+-identifying military personnel.32,33,36 Military personnel of all ages who identify as LGBTQ+, particularly those from communities of color, are at higher risk of experiencing discrimination and adverse mental health consequences from both preventable and unpreventable traumatic experiences during military service. 24,25,33,37-46 Within the LGBTQ+ veteran community, transgender service members are more likely to have experienced discrimination, sexual assault, and homelessness, along with the subsequent adverse mental health outcomes from these experiences.1,10,34,41,43,44,46,47 In-depth interviews of transgender military personnel demonstrated themes of difficulty accessing health care, fear of consequences, and the importance of the therapeutic relationship.4 Further, there is a generally increased perception of mental health stigma in the military, likely decreasing the disclosure of and the treatment-seeking for mental health conditions.30,37 The higher risk of mental health conditions in LGBTQ+ military personnel has been associated with perceived prejudice, lack of psychosocial support, and increased exposure to victimization and violence.24,25,38,48 Research has shown that transgender military personnel have difficulty accessing health care and fear of consequences that may result from requesting gender-affirming care.4 Therefore, it may not be surprising that nearly 97% of transgender veterans undergo gender transition procedures after leaving the military.10 These factors are important to consider since transgender people identify in the military in greater numbers than the general population but have not yet been able to freely access surgical options for gender-affirming care from veteran health services.4 Neurobiological Health of Aging LGBTQ+ Military Personnel Prior studies of LGBTQ+ veterans relied on International Classification of Diseases coding for gender identity disorders to identify transgender individuals57 or natural language processing to identify documentation of cisgender LGBQ military personnel in the clinical notes.57,58 They show that transgender veterans have higher rates of Alzheimer’s disease and cancer44 compared with cisgender veterans. When assessing factors associated with higher COVID-19 severity amongst veterans, minoritized sexual orientation was associated with greater prevalence of stroke, COPD, and asthma.59 Taken together, these studies suggest that LGBTQ+ veterans may have unique health risks that can influence brain health and aging. However, more work needs to be done to better characterize these risk factors and assess their interaction with the psychosocial environment. VHA Efforts to Improve LGBTQ+ Health Care Implications for Social Work Practice Within their organizations, social workers can advocate for staff and leadership training related to providing inclusive care for their LGBTQ+ veterans, particularly gender-affirming care. Social workers can also document instances in which disparities in care are experienced by LGBTQ+ veterans and share them with agency administrators, professional organizations, and community-based LGBTQ+ veteran advocacy organizations. To improve macro practice, social workers who are members and leaders of professional organizations can advocate for these groups to take policy positions on pending legislation to support the implementation of LGBTQ+-affirming policies and improve LGBTQ+ services within the VHA. Social workers who reside in states that do not have Restoration of Honor Acts signed into law can contact state level representatives to support similar legislation. On the federal level, social workers can advocate for implementation of recent changes to policies that support gender-affirming health care to ensure that transgender service members are able to receive safe coordinated continuum of care that is both LGBTQ+-inclusive and veteran centric. Conclusions It’s time to put politics aside and increase access to affirming services and protections for our LGBTQ+ military personnel. Social workers can lead the critical examination of systems of privilege in policy and law that have prevented equitable care for those LGBTQ+ service members and veterans who have served this country. — Z Paige Lerario (they/them/Doctor), MD, is a vascular neurologist and transgender activist. They are a graduate student of social service at Fordham University, and the vice chair of the LGBTQI section of the American Academy of Neurology. Follow their blog at greenburghpride.org. — Roshni Patel, MD, MS, is a neurologist at Jesse Brown VA Medical Center and assistant professor of neurology at Rush University in Chicago. She has special interest in LGBTQ+ health in neurology, Parkinson’s disease, and teleneurology. — Suzanne Marmo, PhD, LCSW, APHSW-C, is an associate professor of social work at Fairfield University. She’s been a licensed social worker since 2001 and a certified advanced palliative and hospice social worker since 2019. Marmo’s clinical expertise includes medical and oncology social work, hospice, palliative care, and working with older adults. Her research interests include palliative and hospice social work, the role of social work in health care organizations, social justice, and inequities in health care systems. — David Vincent, PhD, is the chief program officer with SAGE, where he provides vision, oversight, and leadership to all direct service programs, including care management, housing, behavioral health, and SAGE Center programming. He’s responsible for the conceptualization, development, growth, and management of a broad portfolio of largely government-funded service programs for LGBTQ+ older adults.

References 2. Brown A. About 5% of young adults in the U.S. say their gender is different from their sex assigned at birth. Pew Research Center website. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/06/07/about-5-of-young-adults-in-the-u-s-say-their-gender-is-different-from-their-sex-assigned-at-birth. Published June 7, 2022. Accessed January 13, 2023. 3. Jones JM. LGBT identification in U.S. ticks up to 7.1%. Gallup website. https://news.gallup.com/poll/389792/lgbt-identification-ticks-up.aspx. Published February 17, 2022. Accessed May 19, 2022. 4. Shaine MJD, Cor DN, Campbell AJ, McAlister AL. Mental health care experiences of trans service members and veterans: a mixed‐methods study. J Couns Dev. 2021;99(3):273-288. 5. Gates GJ. How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? eScholarship website. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/09h684x2. Published 2011. Accessed January 30, 2023. 6. Mahowald L. LGBTQ+ Military members and veterans face economic, housing, and health insecurities. Center for American Progress website. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/lgbtq-military-members-and-veterans-face-economic-housing-and-health-insecurities. Published April 28, 2022. Accessed January 30, 2023. 7. Ruben MA, Kauth MR, Meterko M, Norton AM, Matza AR, Shipherd JC. Veterans’ reported comfort in disclosing sexual orientation and gender identity. Med Care. 2021;59(6):550-556. 8. VA health records now display gender identity. VA website https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5753. Published January 12, 2022. Accessed January 30, 2023. 9. Ramirez MH, Sterzing PR. Coming out in camouflage: a queer theory perspective on the strength, resilience, and resistance of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender service members and veterans. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2017;29(1):68-86. 10. Goldbach JT, Castro CA. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) service members: life after don’t ask, don’t tell. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(6):56. 11. Grillot T, Peretz P, Philippe Y. “Wherever the authority of the federal government extends”: banning segregation in veterans’ hospitals (1945–1960). J Am Hist. 2020;107(2):388-410. 12. LGBT demographic data interactive. The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law website. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/visualization/lgbt-stats/?topic=LGBT#demographic. Published January 2019. Accessed January 24, 2023. 13. Stefanovics EA, Grilo CM, Pietrzak RH. Obesity in Latinx and white U.S. military veterans: prevalence, physical health, and functioning. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;155:163-170. 14. Carr MM, Potenza MN, Serowik KL, Pietrzak RH. Race, ethnicity, and clinical features of alcohol use disorder among US military veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Am J Addict. 2021;30(1):26-33. 15. Brenner LA, Forster JE, Walsh CG, et al. Trends in suicide rates by race and ethnicity among members of the United States Army. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(1):e0280217. 16. Kerrigan MF. Transgender discrimination in the military: the new don’t ask, don’t tell. Psychol Public Policy Law. 2012;18(3):500-518. 17. VA health care: better data needed to assess the health outcomes of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender veterans. Government Accountability Office website. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-69. Published October 19, 2020. Accessed January 20, 2023. 18. Belkin A, Bateman G. Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell: Debating the Gay Ban in the Military. Lynne Rienner Publishers; 2003. 19. Wang KH, McAvay G, Warren A, et al. Examining health care mobility of transgender veterans across the Veterans Health Administration. LGBT Health. 2021;8(2):143-151. 20. Fletcher OV, Chen JA, van Draanen J, et al. Prevalence of social and economic stressors among transgender veterans with alcohol and other drug use disorders. SSM Popul Health. 2022;19:101153. 21. Odessky J. LGBTQ+ veterans still suffer harms from “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” ten years after repeal. Legal Aid at Work website. https://legalaidatwork.org/blog/lgbtq-veterans-still-suffer-harms-from-dont-ask-dont-tell-ten-years-after-repeal. Published August 31, 2021. Accessed January 24, 2023. 22. Parks C. Veterans forced out for being gay are still waiting for VA benefits. The Washington Post. July 15, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2022/07/14/dont-ask-dont-tell-va 23. Electeds “Restoration Of Honor Act” signed into law, finally restoring equal rights to LGBTQ+ veterans. Sage Advocacy & Services for LGBTQ+ Elders website. https://www.sageusa.org/news-posts/electeds-restoration-of-honor-act-signed-into-law-finally-restoring-equal-rights-to-lgbtq-veterans. Published November 12, 2019. Accessed February 7, 2023. 24. Moody RL, Savarese E, Gurung S, Rendina HJ, Parsons JT. The mediating role of psychological distress in the association between harassment and alcohol use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual military personnel. Subst Use Misuse. 2020;55(12):2055-2063. 25. Conway MA, Dretsch MN, Taylor MR, Quartana PJ. The role of perceived support and perceived prejudice in the health of LGBT soldiers. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2021;18(3):547-554. 26. Tremblay A, Oliveira JM, Pinard K. Acceptance of transgender veterans in social settings: an experimental study. Psi Chi J Psychol Res. 2021;26(2):113-120. 27. Dunbar MS, Schuler MS, Meadows SO, Engel CC. Associations between mental and physical health conditions and occupational impairments in the U.S. military. Mil Med. 2022;187(3-4):e387-e393. 28. Holliday R, Borges LM, Stearns-Yoder KA, Hoffberg AS, Brenner LA, Monteith LL. Posttraumatic stress disorder, suicidal ideation, and suicidal self-directed violence among U.S. military personnel and veterans: a systematic review of the literature from 2010 to 2018. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1998. 29. Walker S. Assessing the mental health consequences of military combat in Iraq and Afghanistan: a literature review: soldiers mental health. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010;17(9):790-796. 30. Vogt D. Mental health-related beliefs as a barrier to service use for military personnel and veterans: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(2):135-142. 31. Cameron KL, Sturdivant RX, Baker SP. Trends in the incidence of physician-diagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder among active-duty U.S. military personnel between 1999 and 2008. Mil Med Res. 2019;6(1):8. 32. Serier KN, Smith BN, Cooper Z, Vogt D, Mitchell KS. Disordered eating in sexual minority post‐9/11 United States veterans. Int J Eat Disord. 2022;55(4):470-480. 33. Breland JY, Donalson R, Li Y, Hebenstreit CL, Goldstein LA, Maguen S. Military sexual trauma is associated with eating disorders, while combat exposure is not. Psychol Trauma. 2018;10(3):276-281. 34. Grocott LR, Schlechter TE, Wilder SMJ, O’Hair CM, Gidycz CA, Shorey RC. Social support as a buffer of the association between sexual assault and trauma symptoms among transgender and gender diverse individuals. J Interpers Violence. 2023;38(1-2):1738-1761. 35. Bond GR, Al-Abdulmunem M, Drake RE, et al. Transition from military service: mental health and well-being among service members and veterans with service-connected disabilities. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2022;49(3):282-298. 36. Ayer L, Ramchand R, Karimi G, Wong EC. Co-occurring alcohol and mental health problems in the military: prevalence, disparities, and service utilization. Psychol Addict Behav. 2022;36(4):419-427. 37. Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med. 2015;45(1):11-27. 38. Campbell WR, Jahan M, Bavaro MF, Carpenter RJ. Primary care of men who have sex with men in the U.S. military in the post–Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell era: a review of recent progress, health needs, and challenges. Mil Med. 2017;182(3):e1603-e1611. 39. Pelts MD, Albright DL. An exploratory study of student service members/veterans’ mental health characteristics by sexual orientation. J Am Coll Health. 2015;63(7):508-512. 40. Cortes J, Fletcher TL, Latini DM, Kauth MR. Mental health differences between older and younger lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender veterans: evidence of resilience. Clin Gerontol. 2019;42(2):162-171. 41. Aboussouan A, Snow A, Cerel J, Tucker RP. Non-suicidal self-injury, suicide ideation, and past suicide attempts: comparison between transgender and gender diverse veterans and non-veterans. J Affect Disord. 2019;259:186-194. 42. Lucas CL, Goldbach JT, Mamey MR, Kintzle S, Castro CA. Military sexual assault as a mediator of the association between posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among lesbian, gay, and bisexual veterans: military sexual assault, PTSD, and depression. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(4):613-619. 43. Beckman K, Shipherd J, Simpson T, Lehavot K. Military sexual assault in transgender veterans: results from a nationwide survey: military sexual assault in transgender veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(2):181-190. 44. Jasuja GK, Reisman JI, Rao SR, et al. Social stressors and health among older transgender and gender diverse veterans. LGBT Health. 2023;10(2):148-157. 45. Lynch KE, Gatsby E, Viernes B, et al. Evaluation of suicide mortality among sexual minority US veterans from 2000 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2031357. 46. Boyer TL, Youk AO, Haas AP, et al. Suicide, homicide, and all-cause mortality among transgender and cisgender patients in the Veterans Health Administration. LGBT Health. 2021;8(3):173-180. 47. Livingston NA, Lynch KE, Hinds Z, Gatsby E, DuVall SL, Shipherd JC. Identifying posttraumatic stress disorder and disparity among transgender veterans using nationwide Veterans Health Administration electronic health record data. LGBT Health. 2022;9(2):94-102. 48. Klemmer CL, Schuyler AC, Mamey MR, et al. Health and service-related impact of sexual and stalking victimization during United States military service on LGBT service members. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(9-10):NP7554-NP7579. 49. GBD 2017 US Neurological Disorders Collaborators. Burden of neurological disorders across the US from 1990–2017: a global burden of disease study. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(2):165-176. 50. White DL, Kunik ME, Yu H, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder is associated with further increased Parkinson’s disease risk in veterans with traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2020;88(1):33-41. 51. Gardner RC, Byers AL, Barnes DE, Li Y, Boscardin J, Yaffe K. Mild TBI and risk of Parkinson disease: a chronic effects of neurotrauma consortium study. Neurology. 2018;90(20):e1771-e1779. 52. Barnes DE, Byers AL, Gardner RC, Seal KH, Boscardin WJ, Yaffe K. Association of mild traumatic brain injury with and without loss of consciousness with dementia in US military veterans. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(9):1055-1061. 53. Blosnich J, Foynes MM, Shipherd JC. Health disparities among sexual minority women veterans. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(7):631-636. 54. Martinez S, Yaffe K, Li Y, Byers AL, Peltz CB, Barnes DE. Agent Orange exposure and dementia diagnosis in US veterans of the Vietnam era. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(4):473-477. 55. Yang Y, Cheon M, Kwak YT. Is Parkinson’s disease with history of Agent Orange exposure different from idiopathic Parkinson’s disease? Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2016;15(3):75-81. 56. Haley RW. Excess incidence of ALS in young Gulf War veterans. Neurology. 2003;61(6):750-756. 57. Wolfe HL, Reisman JI, Yoon S, et al. Validating data-driven methods to identify transgender individuals in the Veterans Affairs [published online April 12, 2021]. Am J Epidemiol. doi:10.1093/aje/kwab102. 58. Lynch KE, Alba PR, Patterson OV, Viernes B, Coronado G, DuVall SL. The utility of clinical notes for sexual minority health research. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(5):755-763. 59. Lynch KE, Shipherd JC, Gatsby E, Viernes B, DuVall SL, Blosnich JR. Sexual orientation-related disparities in health conditions that elevate COVID-19 severity. Ann Epidemiol. 2022;66:5-12. 60. Remarks by Secretary Denis R. McDonough. Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs website. https://www.va.gov/opa/speeches/2021/06_19_2021.asp. Updated June 24, 2021. Accessed January 24, 2023. 61. Shipherd JC, Kauth MR, Matza A. Nationwide interdisciplinary e-consultation on transgender care in the Veterans Health Administration. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(12):1008-1012. 62. Blosnich JR, Rodriguez KL, Hruska KL, et al. Utilization of the Veterans Affairs’ transgender e-consultation program by health care providers: ixed-methods study. JMIR Med Inform. 2019;7(1):e11695. 63. Hilgeman MM, Lange TM, Bishop T, Cramer RJ. Spreading pride in all who served: a health education program to improve access and mental health outcomes for sexual and gender minority veterans [published online February 3, 2022]. Psychol Serv. doi:10.1037/ser0000604. 64. Shipherd JC, Kauth MR, Firek AF, et al. Interdisciplinary transgender veteran care: development of a core curriculum for VHA providers. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):54-62. |