|

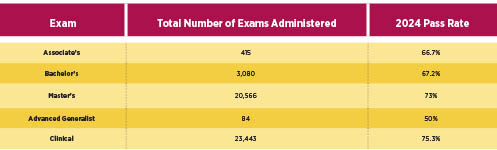

Winter 2026 Issue Social Work Licensure Where We’ve Been, Challenges, and Continued Changes Ahead Social work licensure serves two primary important purposes: protecting the public and ensuring professional standards of practice. The social work profession in the United States was first regulated in the 1940s and continued to expand across the entire United States through the mid 1990s.1 Social work licensure has developed over the course of a century and reflects the profession’s efforts to define its identity, protect the public, and standardize training and practice. This is first noted in the late 1800s through the 1930s as formalized social work education first came into focus. However, at this stage, the profession relied on voluntary standards set by schools and charitable organizations, rather than formal government oversight. The next 20 years brought more of the same but with an increasingly refined focus on professional identity and ethics, as the American Association of Social Workers (AASW) and American Association of Medical Social Workers (AAMSW) established voluntary membership standards. Puerto Rico, as a territory of the United States, implemented the first regulatory processes in 1934.2 The State of California was the first to lead the way with additional professional regulation efforts throughout the 1940s and 1960s. The state attempted to implement the first social work regulatory legislation in 1929, but the bill never passed. A second attempt at regulation, an early version of title protection, came via the employ of a state-level registration system in 1945, which required individuals to register if using the title “social worker.” The state was finally successful in its efforts in 1969, becoming the first to pass a social work licensure law, largely driven by concerns about unqualified practitioners providing psychotherapy to clients.2 The 1970s and 1980s saw an expansion of this focus on regulation with additional states adopting licensure processes while simultaneously implementing practice protection and title protection mandates. This period also saw the American Association of State Social Work Boards (AASSWB) become redesignated as the Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB) with accompanying administration of standardized national licensing exams. This development drove the establishment of licensing processes in each state throughout the 1990s, with a primary focus on clinical practice. This state-by-state development of licensure processes was noted by two former ASWB officers as, “a hodgepodge of different structures for regulating social work.”3 Social work licensure remains a critical issue within the profession for both practitioners and academics alike and continues to evolve. Opportunities to clarify the influence of state licensing on the profession and social work accreditation are key areas of continued focus within the field.4 Social work licensure is critical in defining social workers’ professional identities, duties, prohibited actions, and has changed over time related to societal needs and evolution of the profession. Growing licensure issues remain important to address, including ensuring fair professional standards and access to clinical supervision.5,6 Social work licensure in the United States is distinguished by differences in regulatory structure across different states that involve historical context and political circumstances within different states. Variations in key elements of social work licensure frameworks include, but are not limited to, educational requirements, examination processes, practice definitions, and scope of practice. All 50 states require minimum educational attainment of a social work associate’s degree (ASW), bachelor’s degree (BSW), or a master’s degree (MSW) from a Council on Social Work Education accredited program. Additional requirements also include additional specific coursework completion, targeted internship settings, supervision qualifications, or numbers of completed supervised hours, such as those required for master’s level clinical licensure. The ASWB provides a very useful directory of social work licensure requirements in the United States and Canada differentiated by state, province, or territory.7 ASWB describes differences across these licensure jurisdictions as the “three Es and a fee,” which denotes each state, province, or territory’s unique educational, examination, and experiential licensure requirements and fees. ASWB further explains that each licensure jurisdiction requires social workers to document activities that demonstrate maintenance of competence after initial licensure, which predominantly takes place via continuing education.7 ASWB offers supportive services to the social work profession and others involved in the regulatory process with the goal of ensuring that all social workers protect clients.7 The social work board functions to create and enforce social work licensure rules and regulations, issue licenses, require social workers to maintain state licensure requirements, investigate licensure complaints, and can impose licensure sanctions or revoke licenses, if necessary. The ASWB website offers an overview of licensing requirements and processes, continuing competence guidance, regulatory information, licensing board information, and offers annual meetings and stakeholder engagement for continuous improvement. ASWB has also created the Model Social Work Practice Act that provides legislators with best practice guidance for regulatory development and oversight. Ensuring that competence and licensure requirements are maintained are the individual responsibility of the social worker and not continuing education providers, licensing boards, or professional associations, although each licensing board has some mechanism in place to document and/or attest to and audit compliance with licensure requirements.7 Continuing education time may be measured in clock hours or contact hours, with distinct categories of courses or specific courses that are required for licensure attainment and maintenance. Each state’s licensing board will have further clarifying details about these requirements that should be consulted when applying for initial licensure or when reapplying for relicensure for each renewal cycle. Types of Licenses & Licensure Requirements Emerging Social Work Licensure Topics The Social Work Licensure Compact The professional licensure mobility that the social work licensure compact will provide is not new. Physicians (MDs/DOs), registered and practical nurses (RNs/LPNs), advanced practice nurses (APRNs), physical therapists (PTs), occupational therapists (OTs), emergency medical services (EMS), psychologists, audiologists and speech and language pathologists, registered dietitians (RDs/RDNs), and professional counselors all have some form of interstate licensure compacts.9-15 For additional information about various interstate licensure compacts, you can visit the National Center for Interstate Compacts (NCIC) Database that is searchable by keyword, licensure category, and/or state jurisdiction.16 The Council of State Governments (CSG) and ASWB lead the social work compact effort with the NASW and Clinical Social Work Association (CSWA) as strategic partners.8 Sixteen organizations contributed to the development of model language to be adopted in each state. In February of 2023, a model interstate compact bill was drafted as overseen by CSG. The minimum of seven states adopting the compact has been achieved, but multistate licenses will not be issued for another 12 to 24 months.17 The NCIC licensure map indicates the following states have enacted the licensure compact: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hamshire, New Jersey, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Carolina (with material changes), South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, and Vermont. In addition to the 31 enacted states, the District of Columbia (DC B26-04), Florida (HB 13, SB 74), Massachusetts (S 252), and Pennsylvania (HB 554) have pending legislation under consideration. Several other state jurisdictions do not currently have any current related legislation in development at this time. Current Challenges Concerns have also been raised regarding the licensing exam, as well, specifically concerning equity among historically marginalized groups as well as the appropriateness of exam content. ASWB, in its own analyses conducted by Joy Kim, MSW, PhD, and Michael Joo, MSW, PhD, has noted disparities based on race, ethnicity, and age as seen in significantly lower licensure pass rates among Black, Latinx, and older adults attempting the licensure exam.19 A similar concern has been raised for test takers who are first-generation in the United States and/or those who do not identify English as their primary language. Further questions have been raised concerning the appropriateness of some test questions, particularly on the clinical exam, and concerns about the cost of exam fees and preparation items. Recent changes in ASWB testing processes have also been viewed as having a significant impact on licensure pass rates. Florida, as one example, saw a major change in 2023 concerning the eligibility of individuals to sit for the licensure exam. ASWB changed the long-standing provision that individuals could sit for the exam upon completion of their academic graduate studies. This process was in line with disciplines such as nursing, physician assistant studies, and pharmacy, among others. Individuals in Florida are now ineligible to sit for the licensing exam until at least 18 months postgraduation, which may be another confounding variable in licensure attainment rates. Mental health continues to be a major topic of conversation among advocates and elected officials and compounds the significance of social work licensure. Data from various sources indicate that the US mental health crisis continues to expand across all demographic and socioeconomic groups. Nearly 60 million adults experienced a mental illness in the past year, with approximately 13 million adults reporting serious thoughts of suicide.20 However, a lack of mental health professionals is prevalent across the country. Nationally, it is estimated that there is one mental health provider for every 290 residents. LCSWs comprise one of the largest mental health provider groups in the United States.21 Accordingly, some states prioritize LCSW licensure related to this category of social work related to unmet mental health needs within various state licensure jurisdictions. Licensing Attainment Rates & Changes Ahead

Variations in licensure attainment across states can vary. In addition to the many challenges impacting licensure achievement discussed in this article, the ASWB has convened an LCSW standards setting panel that met in late January of 2026.7 Panelists were required to have a social work degree, hold a valid social work license, and currently be practicing social work. Exam standards were evaluated to establish minimum standards necessary for safe practice in consultation with psychometricians who will collaboratively provide recommendations for passing scores in each examination category. The ASWB also considered ensuring a balanced demographic, practice experience, educational level, and geographic distribution to create a balanced perspective in this licensing exam update process. Social workers should follow these forthcoming exam update recommendations offered by the panel. Conclusion — David Hage, PhD, MSW, LCSW, ACSW, C-ASWCM, CDP, is a licensed clinical social worker currently serving as the MSW Program Director at Florida Gulf Coast University, where he is also an Affiliate Faculty Member of the Shady Rest Institute on Positive Aging. He is the author of numerous book chapters, articles, and his research, teaching, and practice intersect across themes including aging, social work, and higher education. — Thomas P. Felke, PhD, MSW, is professor and BSW Program Director in the Department of Social Work at Florida Gulf Coast University. He is a published author who focuses his research on the use of geographic information systems technologies to examine various social issues, including affordable housing and food insecurity.

Social Work Licensure Resources ASWB Licensure Requirements by State, Province, or Territory: https://www.aswb.org/licenses/how-to-get-a-license/licensing-requirements-by-state-or-province/ ASWB Pass Rate Report (2024): https://www.aswb.org/exam/exam-scoring/exam-pass-rates/ ASWB Pass Rate Interactive Map: https://www.aswb.org/exam/contributing-to-the-conversation/aswb-exam-pass-rates-by-state-province/ Florida Licensure Map (by county): https://fcbhw.org/dashboard Licensure Compact Updates/Map: https://swcompact.org/compact-map/

References 2. Association of Social Work Boards. Manual for new board members. https://www.aswb.org/ 3. National Association of Social Workers. The Encyclopedia of Social Work. National Association of Social Workers Press and Oxford University Press; 2013. 4. Donaldson L, Hill K, Ferguson S, Fogel S, Erickson C. Contemporary social work licensure: implications for macro social work practice and education. Soc Work. 2014;59(1):52-61. 5. Christensen I. Critical reflections on clinical supervision. Adv Soc Work. 2025;25(1):436-453. 6. Howard S, Alston S, Brown M, Bost A. Literature review on regulatory frameworks for addressing discrimination in clinical supervision. Res Soc Work Pract. 2022;33(1):84-96. 7. Association of Social Work Boards website. https://www.aswb.org/. 8. Interstate Licensure Compact. National Association of Social Workers website. 9. Adashi E, Cohen I, McCormick W. The interstate medical licensure compact. JAMA. 2021;325(16):1607. 10. Adrian L. The physical therapy compact: from development to implementation. Int J Telerehabil. 2017;9(2):59-62. 11. Bogulski C, Allison M, Hayes C, Eswaran H. Trends in us state and territory participation in interstate healthcare licensure compacts (2015-2024). Journal of Medical Regulation. 2025;111(1):8-25. 12. Medvec B, Titler M, Friese C. Nurses’ perceptions of licensure compact legislation to facilitate interstate practice: results from the 2022 Michigan nurses’ study. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2023;25(1):14-19. 13. In case you haven't heard. Mental Health Weekly. 2024;34(28):8. https://doi.org/10.1002/mhw.34123 14. Norris C. Nandy P. The nurse licensure compact's effect on telemedicine usage. J Patient Exp. 2023;10:23743735231179060. 15. Willmarth C. Conway S. AOTA–NBCOT® joint initiative: developing the occupational therapy licensure compact. Am J Occup Ther. 2022;76(1):7601070010. 16. NCIC database. National Center for Interstate Compacts website. https://compacts.csg.org/database/ 17. Social Work Licensure Compact. National Center for Interstate Compacts website. https://swcompact.org/ 18. Low Fee Supervision Program. Pennsylvania Society for Clinical Social Work website. https://pscsw.org/content.aspx?page_id=22&club_id=999835&module_id=741230 19. Pass rates in context: an exam report series. Association of Social Work Boards website. https://www.aswb.org/regulation/research/pass-rates-in-context-an-exam-report-series/. Published 2024. 20. Reinert M, Nguyen T, Fritze D. The State of Mental Health in America 2025. https://mhanational.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/State-of-Mental-Health-2025.pdf. Published October 2025. 21. Kourgiantakis T, Sewell K, McNeil S, et al. Social work education and training in mental health, addictions and suicide: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):e024659.

Resource |